Humanity’s timeline in the Americas may need a significant rewrite following the discovery and dating of ancient footprints in New Mexico’s White Sands National Park, suggesting humans arrived at least 8,000 years earlier than previously thought. The research, detailed in a new study published in the journal Science, pushes back the accepted arrival date to between 21,000 and 23,000 years ago, during the height of the last glacial maximum.

The footprints, found in a dried-up lakebed, offer compelling evidence of human presence during a period when ice sheets covered large parts of North America, challenging the long-held Clovis-first theory, which posited that the first Americans arrived around 13,000 years ago. This theory was based on the widespread discovery of distinctive Clovis spear points across the continent. The new findings suggest multiple migrations or a much earlier single migration wave than previously understood.

The research team, led by scientists from the U.S. Geological Survey (USGS) and Bournemouth University in the UK, used radiocarbon dating of seed layers above and below the footprint horizons to determine the age of the impressions. “We present evidence of human occupation of White Sands National Park, New Mexico, from ∼23 to 21 thousand years ago,” the study authors wrote. This dating method provided a robust and reliable timeline for the footprints, strengthening the claim for a much earlier human presence.

The implications of this discovery are profound, forcing archaeologists and anthropologists to reconsider established models of human migration and adaptation in the New World. It raises questions about the routes early humans took to reach the Americas, their survival strategies during a harsh glacial period, and their relationship to the megafauna that roamed the continent at the time.

The footprints themselves are varied, representing a range of individuals, including adults and children. Some show evidence of purposeful activity, such as following game or carrying heavy objects. This provides a glimpse into the daily lives of these early Americans, offering a more intimate and detailed understanding than can be gleaned from stone tools alone. “Several lines of evidence independently indicate that the footprints are human and date between about 23,000 and 21,000 calendar years ago,” stated the research team.

The site at White Sands National Park continues to be a rich source of information about the earliest Americans. Ongoing research and excavations are expected to uncover more artifacts and evidence that will further refine our understanding of this pivotal period in human history.

Challenging the Clovis-First Theory

For decades, the Clovis-first theory dominated archaeological thinking about the peopling of the Americas. This theory proposed that the Clovis culture, characterized by its distinctive fluted spear points, represented the first human inhabitants of North America. The oldest known Clovis sites were dated to around 13,000 years ago, leading to the assumption that humans had only arrived in the Americas shortly before that time, migrating from Siberia across the Bering Land Bridge, which connected Asia and North America during the last ice age.

However, in recent years, a growing body of evidence has challenged the Clovis-first model. Pre-Clovis sites, such as Monte Verde in Chile, which dates back to at least 14,500 years ago, have demonstrated that humans were present in the Americas thousands of years before the Clovis culture emerged. The White Sands footprints provide further compelling evidence against the Clovis-first theory, pushing back the timeline of human arrival by as much as 8,000 to 10,000 years.

“The White Sands footprints add another layer to the story, suggesting that humans were present in North America much earlier than previously thought and that the Clovis culture was not the beginning of the story,” said Dr. Sally Reynolds, a co-author of the study from Bournemouth University.

The discovery forces a re-evaluation of migration routes and the timing of human dispersal across the Americas. It suggests that early humans may have arrived in multiple waves, or that the initial migration occurred much earlier than previously believed, with subsequent groups developing distinct cultural adaptations, such as the Clovis technology.

Dating the Footprints: A Robust Methodology

The accurate dating of the footprints was crucial to the credibility of the research. The team employed radiocarbon dating, a well-established method for determining the age of organic materials, to analyze seed layers found both above and below the footprint horizons. Radiocarbon dating measures the decay of carbon-14, a radioactive isotope of carbon, in organic samples. By comparing the amount of carbon-14 remaining in a sample to its initial concentration, scientists can estimate its age.

The seed layers provided ideal samples for radiocarbon dating because they contained organic material that was deposited contemporaneously with the footprints. By dating the seed layers above and below the footprint horizons, the researchers were able to establish a precise chronological framework for the human activity at the site.

Initially, there were concerns about the accuracy of radiocarbon dating in the area, as ancient carbon reservoirs can sometimes skew the results. However, the researchers conducted rigorous tests and comparisons to ensure the reliability of their dates. They compared the radiocarbon dates from the seed layers to dates obtained from other sources, such as pollen records and geological data, to verify the accuracy of their findings. These tests corroborated the original dates, solidifying the conclusion that the footprints were between 21,000 and 23,000 years old.

“Recognizing the potential for inaccuracies from old carbon reservoirs, we compared the radiocarbon ages from the seeds with optically stimulated luminescence ages of quartz grains and the 14C ages of charcoal. The agreement among these independent chronometers confirms the accuracy of our radiocarbon ages,” explained the study authors.

Life During the Last Glacial Maximum

The discovery of human footprints dating back to the Last Glacial Maximum raises intriguing questions about how early Americans survived in such a harsh environment. During this period, vast ice sheets covered much of North America, making survival challenging for both humans and animals.

The climate was significantly colder and drier than it is today, with limited vegetation and resources. Early humans would have had to adapt to these conditions by developing specialized hunting techniques, crafting warm clothing, and finding shelter from the elements.

The White Sands National Park, despite its current desert landscape, was a different environment during the Last Glacial Maximum. A large lake, known as Lake Otero, existed in the Tularosa Basin, providing a source of water and attracting animals. The footprints suggest that humans were actively hunting or scavenging around the lake, likely targeting large mammals such as mammoths, mastodons, and giant ground sloths.

“The area was likely a refuge for both humans and animals during the Last Glacial Maximum,” said Dr. David Bustos, the park’s resource program manager. “The lake provided a reliable water source, and the surrounding grasslands supported a variety of large mammals.”

The discovery of footprints from both adults and children suggests that families were present at the site, indicating a degree of social organization and cooperation. The footprints also provide clues about the activities that early humans were engaged in, such as hunting, gathering, and transporting goods. Some footprints show evidence of individuals carrying heavy loads, while others suggest that people were tracking animals.

Implications for Migration Routes

The White Sands footprints also have significant implications for understanding the routes that early humans took to reach the Americas. The traditional view is that humans migrated from Siberia across the Bering Land Bridge, which connected Asia and North America during the Last Glacial Maximum when sea levels were lower. However, the presence of humans in New Mexico as early as 23,000 years ago raises questions about the timing and feasibility of this route.

One possibility is that humans migrated along the Pacific coast, using boats or other watercraft to travel south along the edge of the ice sheets. This coastal migration route would have provided access to marine resources and may have been easier to navigate than the interior route through the ice-covered continent.

Another possibility is that humans migrated across the interior of North America, following ice-free corridors that opened up between the ice sheets. These corridors would have provided a pathway for humans and animals to move south, although the conditions would have been harsh and challenging.

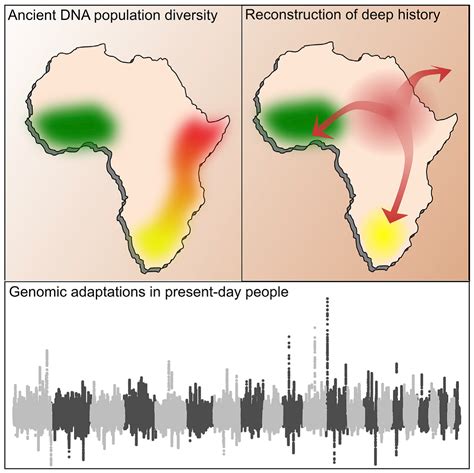

The White Sands footprints do not provide definitive evidence for either migration route, but they do suggest that humans were present in North America much earlier than previously thought, which makes both the coastal and interior routes more plausible. Future research, including the discovery of additional pre-Clovis sites and the analysis of ancient DNA, will be needed to determine the precise routes that early humans took to reach the Americas.

Future Research and Discoveries

The White Sands National Park continues to be a site of ongoing research and discovery. Scientists are conducting further excavations and analyses to learn more about the early Americans who left their footprints in the ancient lakebed.

One of the key goals of future research is to identify more artifacts and evidence that can provide additional insights into the lives of these early humans. This includes searching for stone tools, animal bones, and other remains that can shed light on their diet, technology, and culture.

Another important area of research is the reconstruction of the environment at White Sands during the Last Glacial Maximum. Scientists are studying pollen records, geological data, and other sources of information to understand the climate, vegetation, and animal life that existed at the time. This information will help to provide a more complete picture of the world that early Americans inhabited.

The White Sands footprints have opened up a new window into the past, challenging long-held assumptions and raising new questions about the peopling of the Americas. As research continues, we can expect to learn even more about these early humans and their remarkable story of survival and adaptation.

The park service is committed to protecting the site and ensuring that it is available for future generations to study and appreciate.

Broader Context and Implications

The discovery at White Sands is not an isolated event. It’s part of a growing trend in archaeology and genetics that paints a more complex picture of the peopling of the Americas than the Clovis-first model allowed. Discoveries at sites like Monte Verde in Chile and Paisley Caves in Oregon, along with genetic studies of Native American populations, have already suggested a pre-Clovis presence.

The White Sands footprints provide some of the most compelling and direct evidence yet, thanks to the robust dating methodology and the sheer volume of footprints. The implications extend beyond the Americas, potentially impacting our understanding of human dispersal patterns across the globe during the late Pleistocene. If humans were able to adapt and thrive in the challenging environment of glacial North America as early as 23,000 years ago, it suggests a remarkable degree of resilience and adaptability that may have facilitated their spread to other parts of the world.

The findings also underscore the importance of interdisciplinary research. The White Sands study involved collaboration between archaeologists, geologists, paleontologists, and other specialists. This collaborative approach is essential for unraveling the complex history of human origins and migrations.

The controversy surrounding the peopling of the Americas is far from settled. Some researchers remain skeptical of the pre-Clovis evidence, arguing that the dating methods may be unreliable or that the artifacts may not be of human origin. However, the growing body of evidence, including the White Sands footprints, is increasingly difficult to ignore. The debate is likely to continue for years to come, but it is a healthy debate that is pushing the boundaries of our knowledge and challenging us to rethink our assumptions about the past.

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQ)

-

What is the significance of the White Sands footprints?

The White Sands footprints are significant because they provide compelling evidence that humans were present in North America between 21,000 and 23,000 years ago. This is thousands of years earlier than previously believed, challenging the long-held Clovis-first theory, which posited that the first Americans arrived around 13,000 years ago. The discovery forces a re-evaluation of migration routes, the timing of human dispersal across the Americas, and how early humans adapted to the harsh conditions of the Last Glacial Maximum.

-

How were the footprints dated?

The footprints were dated using radiocarbon dating of seed layers found both above and below the footprint horizons. Radiocarbon dating measures the decay of carbon-14, a radioactive isotope of carbon, in organic materials. The researchers compared the radiocarbon dates from the seeds with optically stimulated luminescence ages of quartz grains and the 14C ages of charcoal. The agreement among these independent chronometers confirms the accuracy of the radiocarbon ages. This method provided a robust and reliable timeline for the footprints, strengthening the claim for a much earlier human presence.

-

What was the environment like in White Sands during the Last Glacial Maximum?

During the Last Glacial Maximum, White Sands National Park was a different environment than it is today. While now a desert, it was then characterized by a large lake, known as Lake Otero, within the Tularosa Basin. This lake provided a source of water, attracting animals like mammoths, mastodons, and giant ground sloths. The surrounding grasslands would have supported a variety of large mammals, making the area a potential refuge for both humans and animals during a period when much of North America was covered in ice sheets. The climate was colder and drier than today, with limited vegetation, requiring early humans to develop specialized hunting techniques and adapt to the harsh conditions.

-

What does this discovery mean for the Clovis-first theory?

The discovery significantly weakens the Clovis-first theory. For decades, this theory dominated archaeological thinking, proposing that the Clovis culture, characterized by its distinctive fluted spear points, represented the first human inhabitants of North America, dating back to around 13,000 years ago. The White Sands footprints provide evidence of human presence 8,000 to 10,000 years before the Clovis culture emerged, suggesting that humans arrived in the Americas much earlier. It suggests that the Clovis culture was not the beginning of the story and that early humans may have arrived in multiple waves or that the initial migration occurred much earlier, with subsequent groups developing distinct cultural adaptations, such as the Clovis technology.

-

What are the possible migration routes early humans might have taken to reach White Sands?

The White Sands footprints raise questions about the routes that early humans took to reach the Americas. The traditional view is that humans migrated from Siberia across the Bering Land Bridge. However, the presence of humans in New Mexico as early as 23,000 years ago suggests alternative or earlier migration routes. One possibility is a coastal migration route along the Pacific coast, using boats to travel south along the edge of the ice sheets. Another possibility is migration across the interior of North America, following ice-free corridors that opened up between the ice sheets. The White Sands footprints do not definitively prove either route, but they suggest humans were present in North America much earlier, making both routes plausible. Further research is needed to determine the precise routes.

The Broader Scientific Community Reaction

The findings at White Sands have been met with a mixture of excitement and cautious skepticism within the scientific community. While many researchers acknowledge the significance of the discovery and the robust dating methodology employed, some remain hesitant to completely abandon the Clovis-first model. Their concerns often revolve around the potential for contamination or inaccuracies in the radiocarbon dating process, even though the researchers took considerable steps to mitigate these risks.

Some archaeologists have called for additional lines of evidence to support the footprint data, such as the discovery of more pre-Clovis artifacts at the site or in nearby areas. They argue that while the footprints provide compelling evidence of human presence, they do not necessarily tell the whole story. For example, it is possible that a small group of humans arrived in the Americas very early, but that they did not leave a significant archaeological footprint until the Clovis period.

However, the majority of researchers agree that the White Sands footprints are a significant contribution to our understanding of the peopling of the Americas. They represent some of the most convincing evidence yet of a pre-Clovis presence, and they have stimulated renewed interest in the search for earlier sites and artifacts. The discovery has also highlighted the importance of interdisciplinary research, bringing together experts from different fields to tackle complex questions about the past.

The debate over the peopling of the Americas is likely to continue for years to come, but the White Sands footprints have undoubtedly shifted the paradigm. The Clovis-first model is no longer tenable, and researchers are now actively exploring alternative scenarios that can account for the growing body of evidence of a pre-Clovis presence. This is a healthy process that is driving innovation and discovery in the field of archaeology.

Ethical Considerations and Preservation

The discovery of the White Sands footprints raises important ethical considerations regarding the preservation and management of cultural heritage sites. The footprints are a fragile and irreplaceable resource that provides valuable insights into the lives of early Americans. It is essential that these footprints are protected from damage and destruction, both from natural processes and human activities.

The National Park Service, which manages White Sands National Park, is responsible for protecting the footprints and ensuring that they are available for future generations to study and appreciate. The park service has implemented a number of measures to protect the footprints, including restricting access to sensitive areas, monitoring the condition of the footprints, and conducting research to understand the threats to their preservation.

However, the task of protecting the footprints is not without its challenges. The arid environment of White Sands National Park is prone to erosion, which can damage or destroy the footprints. Climate change is also a concern, as rising temperatures and changes in precipitation patterns could exacerbate erosion and other threats to the site.

In addition to physical protection, it is also important to consider the ethical implications of studying and interpreting the footprints. Researchers have a responsibility to consult with Native American tribes and communities who may have ancestral ties to the site. It is important to respect the cultural values and beliefs of these communities and to ensure that their voices are heard in the interpretation of the footprints.

The White Sands footprints are a reminder of the long and complex history of human presence in the Americas. By protecting and studying these footprints, we can learn more about our shared past and gain a deeper appreciation for the resilience and adaptability of the human spirit.